The Spinning Wheel of Death – Doomsayers and AI

I hope that you’ve never experienced the Spinning Wheel of Death. But if you are a Mac user you may have had that gut wrenching moment of despair when everything freezes, the app you are using judders to a halt, and all you can do it watch, hypnotised by the rainbow wheel that spins, and spins and spins…

What’s making me think about this little beach ball of evil this sunny morning? I saw on my Twitter feed that in March TechEmergence published the results of interviews with 40 AI experts on what they think is the most likely AI risk in the next 20 years.

TechEmergence have displayed this data in a rather neat spinning wheel inforgraphic made up of 33 of the researchers and their bio pics, grouping them and some of their one-liners into seven categories of risk (you can subscribe to be sent the complete data set as a spreadsheet, which also includes longer term predictions). These categories are:

- None Given (6 researchers)

- Malicious Intent of AI (1)

- General Mismanagement of AI Technology (5)

- Superintelligence (2)

- Surveillance/Security (3)

- Automation/Economy (12)

- Killer Robots (4)

The respondants are a mix of technological experts and more philosophically inclined researchers like Dr Peter Boltuc.

Ignoring the fact that this wheel of predictions could easily be submitted to the Congrats, You Have an All Male Panel! Tumblr (I found Joanne Pransky hidden away in the data set but not on the infographic), I have a few issues with this research and its presentation.

First, the coding. In particular the category of ‘None given’ for answers on risk like:

“The revelation that human minds may not be as wonderful as we all thought, leading to the inevitable humiliation and denial that accompanies significant technological breakthroughs.” (Dr. Stephen Thaler)

This kind of existential risk might be more worrisome than just assuming Humanity will go through some sort of ’emo’ phase as its place in the ‘centre’ of the universe is displaced. Responses could be far more significant, including but not limited to: putting new technology to use in new religious narratives as this once stable category (our singular superiority) is displaced. If you don’t think the emergence of these narratives can be significant consider the impact of long distance communications (ie the telegram and Morse Code) on the emergence of spiritualist ideas about our ability to communicate with an ‘afterlife’. This communication might be an idea that you do not subscribe to, but it has had an impact on society, around the world, since the 1900s. Not least in the development of the New Age movement and in the emergence of specific New Religious Movements that aim to connect their believers with an afterlife.

“The biggest risk is some sort of weaponization of advanced narrow AI or early-stage AGI. This wouldn’t have to be killer robots, it could e.g. be an artificial scientist narrowly engineered to create syntheticpathogens— or something else we’re not currently worrying about. Human narrow mindness and aggression, aided by AI tools that are more narrowly clever than generally intelligent or conscious. That’s what we should be worrying about, if anything. Fear of advanced AGI is mostly just generic “fear of the unknown”, and tends to be based on insufficiently deep thinking about the open-ended nature of intelligence.” (Dr Ben Goertzel)

Again, here’s a whole bunch of risks. The distinction between narrow AI and advanced AI is a key one to make, and not one expressed by TechEmergence in its introduction or framing of this work. Clarity on such terms matters: words impact the conceptions people have of this risk that TechEmergence is trying to give a picture of. Likewise, coding military applications of AI as ‘Killer Robots’is leading, and also not a fair description of comments like:

“Intelligent drones bringing military competition to the next level.” (Dr. Peter Boltuc)

The ‘Killer Robots’ trope owes a fair deal to films like Terminator – images from which are regularly wheeled out in articles on Artificial Intelligence because, according to a journalist I spoke to recently about this, a “sense of narrative investment, if not baggage, is valuable, I think. Otherwise the robots can feel inert”. TechEmergence however makes claims to some neutrality: in the dataset is a page of disclaimers, including:

“It’s remarkably important for me to make it clear that I am neither a techno-pessimist or a techno-optimist. In general, we don’t pursue interviews or ask questions to garner “cool” or “futuristic” answers. Rather, our aim is to get a legitimate lay of the land from researchers and experts who know what they’re talking about. TechEmergence exists to proliferate the grander conversation rather than to push a particular set of beliefs or predictions.”

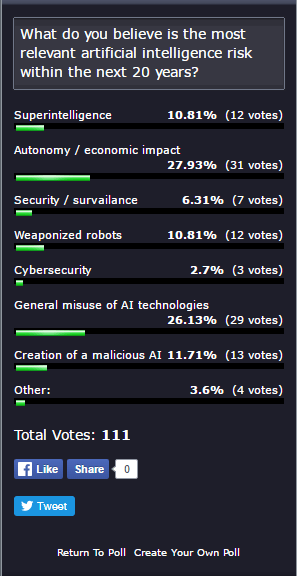

But words have impact. The Spinning Wheel of Death (see, this post has biased you to thinking these researchers are all doom-sayers…) rests above a survey for readers, dividing risk again into categories, with ‘None given’ replaced by ‘Other’ with a write in box for responses. So far there have been 111 responses:

This survey does not directly match the categories applied to the AI researchers’ answers. We can note that ‘Killer Robots’ has been replaced with ‘weaponized robots’, and ‘Cybersecurity’ seems to be in the place of ‘Malicious Intent of AI’, although these are hardly equivalent. It would also be interesting to see what was written in for those ‘Other’ answers.

I think what most drew me to the Spinning Wheel of Death is that – in words that its creator uses when discussing the neutrality of TechEmergence on the subject – is that its about beliefs and predictions. The voices involved are key figures in the consideration and development of AI, so they speak from experience. But we don’t really know what risks lie ahead, this is crystal ball gazing.*

And I find that extremely fascinating. Not quite Spinning Wheel of Death hypnotising perhaps. But remember, that ball only appears when someting has gone wrong with our advanced tech, something perhaps unpredictable. Just like AI.

*Another spiritual ‘technology’ influenced by real world developments in communications tech at the time

Don’t Read This Post

I’ve recently had a paper accepted for the 2016 ‘Denton’ Conference on Implicit Religion. This is the first piece of research coming out of the Faraday AI and Robotics project, so its very exciting to have been accepted!

Here’s the abstract, and once you read it and learn about Roko’s Basilisk you’ll know why I titled this post as I have!

Roko’s Basilisk, or Pascal’s? Thinking of Singularity Thought Experiments as Implicit Religion

“The original version of [Roko’s] post caused actual psychological damage to at least some readers. This would be sufficient in itself for shutdown even if all issues discussed failed to be true, which is hopefully the case.

Please discontinue all further discussion of the banned topic.

All comments on the banned topic will be banned.

Exercise some elementary common sense in future discussions. With sufficient time, effort, knowledge, and stupidity it is possible to hurt people. Don’t.

As we used to say on SL4: KILLTHREAD.” – Eliezer Yudkowsky, July 2010

This KILLTHREAD command came in response to a post written only four hours earlier on the ‘LessWrong’ community blog by ‘Roko’. A post which had introduced a rather disturbing idea to the other members, who are dedicated to “refining the art of human rationality”, according to LessWrong literature.

Roko had proposed that the hypothetical, but inevitable, super-artificial intelligence often known as the ‘Singularity’ would, according to its intrinsic utilitarian principles, punish those who failed to help it, or to help to create it. Including those from both its present and its past through the creation of perfect virtual simulations based on their data. Therefore, merely knowing about the possibility of this superintelligence now could open you up to punishment in the future, even after your physical death. In response to this acausal threat, the founder of LessWrong, Eliezer Yudkowsky responded with the above dictat, which stood for over five years.

Roko’s Basilisk, as this theory came to be known for the effect it had on those who ‘saw’ it, has been described by the press in florid terms as “The Most Terrifying Thought Experiment of All Time!” (Slate, 2014). It has also been dismissed by members as either based on extremely flawed deductions, or as an attempt to incentivise greater “effective altruism” – directed financial donations for the absolute greatest good. In this case, donation specifically to MIRI, the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, which works towards developing a strictly human valued orientated AI, and which is also directly linked to the LessWrong forum itself. Others have dismissed it as a futurologist reworking of Blaise Pascal’s famous wager, or as just a fanciful dystopian fairytale.

This paper will not debate the logic, or validity, of this thought experiment. Instead it will approach the case of Roko’s Basilisk with a social anthropological perspective to consider how its similarities with theologically inclined arguments highlights the moral boundary making between the religious and the secular being performed by rationalist forums of futurologists, transhumanists and Singularians such as LessWrong and the AI mailing list ‘SL4’ that Yudowsky referred to. This paper also raises wider questions of how implicitly religious thought experiments can be, and how this boundary making in apparently secular thought communities can be critically addressed.

Slate (2014) “The Most Terrifying Thought Experiment Of All Time: Why Are Techno-Futurists So Freaked Out By Roko’s Basilisk?”, available at http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/bitwise/2014/07/roko_s_basilisk_the_most_terrifying_thought_experiment_of_all_time.html (accessed 22/02/2016)

Sorry, but I did warn you. /KILLTHREAD

Make a Religion Check

This week I am mostly concentrating on writing one of my papers for the 2015 IAHR (International Association for the History of Religions) conference later this month. The abstract for my paper is as follows:

When Galaxies Collide: Jediism’s Revisionism in the Face of Corporate Buyouts and Mythos ‘Retconning’

In 2001 thousands of people wrote in ‘Jedi’ for the religious question in censuses around the world. While for many this was a joke or parody, small groups of genuine believers have formed their own Jedi religion, both on and offline. This paper explores their revisionism in response to the rewriting, or ‘retconning’, of the Star Wars Universe by George Lucas, its creator, and by Disney, which bought that universe in 2012 for $4 billion. In 1999 Lucas introduced micro-organisms as the true indicators of Jedi ability. Disney’s purchase of Lucasfilm has led to a large reduction in the size of the universe itself as the new owners make and release new films. This paper will discuss and contextualise the coping strategies of the real world Jedi in response to these changes

The tensions that arise when New Religious Movements draw on trademarked or ‘owned’ fantasy materials are a particular interest of mine. A paper I gave at the 2013 BASR (British Association for the Study of Religion) conference on real world Jedi and their responses to intellectual property disputes has since become a chapter in a new book from Ashgate on Legal Pluralism. However, the IAHR paper on Jediism considers what happens when the source material isn’t only trademarked, but also changed or deleted by the creators/owners. I won’t go into my findings much in this post (spoilers!) but the TL:DR version is that NRMs like Jediism will necessarily move away from the source material in order to protect their unique re-imagination of on it. Further, they’ll make a distinction between themselves and those who follow the ‘rules’ of canon and canon productions such as games. In particular I’ve seen a strong demarcation made by real world Jedi between themselves and those fans of Star Wars who “live action role play” (LARP) as Jedi, who are wearing the same robes and swinging the same plastic light sabers as the real world Jedi knights.

I’ve recently found another example of this boundary making in the discourse of other kinds of role players who seek to distinguish themselves from those of a more religious persuasion. I have had a very enjoyable time over the past few days reading Joseph Laycock’s Dangerous Games: What the Moral Panic over Role Playing Games Says about Play, Religion and Imagined Worlds. It might seem strange to enjoy reading an account of Satanic Ritual Abuse accusations! But I first played Dungeons & Dragons in the early 1990s and this book is a wonderful nostalgia trip for anyone who spent their teen years being given funny looks for knowing what a d12 was (note 2.)

With regards to this demarcation process, Laycock states that, “Role players have a vested interest in distancing themselves from occultists in response to the claims of moral entrepreneurs, while occultists desire to be taken seriously and not associated with a game of fantasy” (Laycock, 2015: 201). Change the word ‘occultists’ to something a little broader like ‘believers’ and change ‘games’ to ‘fantasy fiction’, and you get the same boundary work that I claim real world Jedi are engaged in. But why is this boundary making necessary?

In Dangerous Games Laycock delves into the history of a culture war that any fantasy role player of the 1970s-1990s would have heard of. Not from the bards of the taverns they frequented in game, but from the pages of the salacious tabloids that enthusiastically reported on the “Satanic trap” that was Dungeons & Dragons. A full on “moral panic” (Cohen, 1972) blew up during these decades as Dungeons & Dragons was blamed for the murderous activities of teenagers, for introducing children to the occult, for being a cover for a Satanic conspiracy, and worst of all, for distracting from God’s own reality. The “moral entrepreneurs” making the accusations, as Laycock terms them, were initially from the medical community and at first pathologized this ‘delusion’, considering it to be a form of madness. But they were soon predominantly Christians of an evangelical or fundamentalist persuasion. Examples include the organisation Bothered about Dungeons and Dragons (BADD), the tracts of conservative evangelical Jack Chick, and the best-selling book, Mazes and Monsters, which became a made-for-TV movie starring Tom Hanks in 1982. The final scene presents Hank’s character as hopelessly lost in the world of his imagination, his personality forever supplanted by his LARP character’s:

Laycock develops a very interesting argument about the regulation, and the confusion, of the realms of reality, fiction and fantasy in this book. I won’t be able to do it full justice here (read the book!), but drawing on the work of Peter Berger, Erving Goffman, and Gary Alan Fine, he argues that three modes of comprehension, or frames, are at play simultaneously during any fantasy role-playing game. First, there is the world of daily life, or ‘reality’. Second, the rules of the game provide a framework for another level of vocabulary and understanding. Finally, there is the content of the fantasy world in which the players are placing themselves. Thus, the following sentence, uttered by a player during a game, makes use of all three frames and we can discern which is which: “Are you friend or foe? I’m rolling for charisma. Pass the chips.” (note 3)

“Most of the time” Laycock says, “players are able to move fluidly back and forth between the three frames without confusion” (2015: 10). However, moral entrepreneurs, the accusers of the Satanic Abuse craze, appear unable to make these fluids shifts of frame. They read source texts for D&D such as the Monster Manual and Deities and Demigods and deduced that through the game children were being taught how to summon real archfiends, succubi, or imps. Laycock says, “outside observers sensed a religious function at play in D&D but lacked the background in religious studies to articulate how exactly the game related to their understanding of religion as a category. Claims that role-playing games are ‘occult’ were, in part, attempts to express this idea.” (Laycock, 2015: 52). He blames this inability to articulate Dungeons & Dragons as fantasy or ‘play’ on the conservative move to biblical literalism: in response to the modernist claim that the bible itself is a ‘myth’. He states that they also rejected all forms of fiction as distracting, time wasting or as a heretical avoidance of the real world that God had given us. There were of course some Christians, Tolkien in particular, who saw fiction as a sub-creation, hand in hand with God. However, the materialist turn of these particular types of moral entrepreneurs meant that they lost the ability to move easily between these three frames, and that the fantasy of Dungeons & Dragons was only understandable to them as a real, demonic, conspiracy.

Further, Laycock argues that fantasy is dangerous to such literalists because, as in Huizinga’s work on Homo Ludens (‘Man the Player’) the rules of games “formed the basis of myth and ritual, which in turn led to the development of law, commerce, craft, art, and science.” (Laycock, 2015: 9). The fantasy of Dungeons & Dragons, the imaginative play, is the same kind of world making. But this is a world making that has effects outside the game: changing the first of the three frames by encouraging personal, radical, agency, and by allowing “the players a mental space from which to reassess their worlds” (Laycock, 2015: 27). And at this one step removed it is all the clearer that the wider world, and its parts such as religion, is just as socially constructed as the world in which they are gaming.

Finally, the literalist’s inability to move between these frames of imagination and reality, and remain aware of which is which, doesn’t mean that they are entirely without narrative ability. Laycock argues that the moral entrepreneur is engaged in the same process of re-enchantment as the gamer. Both seek to be magically powered heroes, one in the game where they face demons that they know to be made up (by the DM, by the creator of the game system, and/or by other historical storytellers), and the other “battles the imagined forces of evil as occult crime investigators and exorcists […] with nowhere to go, their heroic fantasies are imposed on the real world as conspiracy theories.” (Laycock, 2015: 242-243).

However, this particular moral panic cannot be dismissed as a case of a minority of moral entrepreneurs simply failing to recognise fantasy when it is in front of them. Their response to the ‘cult’ of Dungeons & Dragons is a part of larger, intentional, categorisation of behaviour as deviant by a hegemony, seen also in the Anti-Cult movements’ response to the New Religious Movements that they encountered at around the same time as these Satanic Abuse accusations. “At stake in the claims made about fantasy Role Playing Games is the problem of how such categories as ‘fantasy’ and ‘reality’ and ‘madness’ and ‘sanity’ are defined. The ability to define these categories is the single most powerful form of control over the social order” says Laycock (2015: 9). In the case of the real world Jedi in particular the accusation of delusion is regularly framed through parody, and I’ve argued elsewhere that the initial moral panic in the face of New Religious movements has largely become a moral parody. Laycock ties the decline of the Satanic Abuse accusations against Dungeons & Dragons to the 2001 terrorist attacks, and the arrival of a new enemy that could be tied into demonic conspiracy theories. More readily, perhaps, than Dungeons & Dragons players who were only rarely linked to violent acts (and even if they were, the ‘D&D defence’ was increasingly being dismissed by courts who were better able to recognise fantasy). Likewise, the pernicious ‘cults’ are now more likely to be derided. Even atrocities like the Sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway by Aum Shinrikyo (1995) are fading from memory in the face of more recent attacks by more ‘mainstream’ religious fundamentalists.

So it was interesting then to see a group of Dungeon & Dragons fans describing themselves as a ‘cult’ recently, apparently adopting the language of the moral entrepreneurs.

Before I explain how I saw this, I will provide a little context. I have been getting back into table-top roleplaying in the past few months (so it’s really not surprising that I picked up Laycock’s book!). I played Dungeons & Dragons, among other games, in the 1990s. But unlike most people who first discover D&D at university I pursued other hobbies when I went, and drifted away from it. Recently I have started attending a games night at a bookshop in Cambridge, and I have been involved in a few one off games of Dungeon World, a fantasy role-playing game that I will be DM-ing for the first time on 15th August. I was inspired to get back into playing by a web series called Critical Role where a group of professional voice actors from Los Angeles are recorded playing Dungeons & Dragons live each week. The enthusiasm of the show’s fans on social media is immense, and many of them are involved in fantasy projects of their own inspired by the canon of the show, e.g. fanart, fanfiction, music production and their own role playing campaigns. Parallels could of course be drawn with various other fan projects of the imagination inspired by canon, in particular the Star Wars fandom that the real world Jedi of my research are moving away from.

It was interesting therefore to see a few members of the Critical Role fandom describing it as a cult, unintentionally repeating the rhetoric of the anti-Dungeons & Dragons crusaders presented in Laycock’s account. As quoted above, gamers have a “vested interest” in separating themselves from the occultist, in “response to the claims of moral entrepreneurs” (2015: 201). Is it that the moral entrepreneurs, distracted by other conspiracies since 2001, are no longer on the radar of Dungeons & Dragons players who can use the term cult more freely? Afterall cult, in the sense of pop culture is adopted widely. Is this how are they using the term? Looking at the context it seemed to be a rather playful, or even self-paroding, usage, referring to religion:

“So I’m part of a cult now! Cool! Also seeing all of the guys so excited is one of the best parts of the show 🙂 #CriticalRole”

“Shit we’re in a cult. #Critters #CriticalRole “[a Critter is a Critical Role fan]

This seems to me to be another example of the skilful play with interpretative frames. These individuals are playing with the role of the ‘cult follower’ in their descriptions of themselves as fans, while remaining aware that they are not in fact in a ‘cult’. Of course, a moral entrepreneur reading these comments without the ability to discern fantasy from reality might read this as a form of confession. Or perhaps I am wrong, and I should be watching out for signs that they are building altars to the Critical Role players in their bedrooms?! There is much academic debate as to where the line between fandom and religion can be drawn (a recent conference I was unable to attend dealt with this issue). However, I am inclined to see this as another example of role-playing, and Laycock quotes Sartre, who famously said that “existence precedes essence”, to argue that “ultimately we are all roleplayers, whether we want to be or not” (Laycock, 2015: 237) (note 4). Which might perhaps disappoint the Jedi in their attempts to distance themselves from the LARPers of the Star Wars fandom, as well as the changes in canon that the Star Wars buy out has wrought.

Notes:

1. The title of this post, “Make a Religion Check”, refers to how gamers can roll dice to find out if they “remember a useful bit of religious knowledge or to recognize a religion-related clue.” (D&D Wiki). This blog post is my own religion check that I made in response to the ‘cult’ quotes… and the result informs my conference paper. Lets hope I level soon.

Yes, that comment WAS me “moving fluidly between frames”. You’re welcome.

2. A small note needs to be made of the overlap between academics and role-players, particularly in the Religious Studies field. I propose further research is necessary on this correlation… ideally at an academic conference, over a game of D&D.

3. As my esteemed colleague Ethan Quillen would point out, everything, including the first frame, is fiction. Laycock uses Berger to admit that there are a multiplicity of constructed worlds, and his use of Sartre also supports this view that we are all creating fictions/role playing. “Pass the chips” is therefore no more ‘real’ than “Are you friend or foe”.

4. I told you Ethan, I told you!!!

Short Video About my Research

Here’s a short video I made with the college reporter about my PhD research (go to no.3 on the playlist… for some reason the link plays all…)

Generation Hex – Day Workshop, 10th September 2015, Cambridge UK.

My very good friend, and fellow academic, Jonathan Woolley, is joint convening a workshop in Cambridge on the contemporary study of Paganisms. Please take a look 🙂

Generation Hex – the Politics of Contemporary Paganism

Convenors: Jonathan Woolley, University of Cambridge; Kavita Maya, SOAS, University of London; Elizabeth Cruze, Druid Elder and Activist.

Venue: Seminar Room, Division of Social Anthropology, Free School Lane, Cambridge, CB2 3RF.

Date: 09.30 – 16.30, 10th September 2015.

Themes: Paganism and Nature Spirituality; Goddess Spirituality and Feminism; Theology and Thealogy; Cultural Appropriation; Feminist Theory; Gender and Sexuality; Ecopolitics and Environmentalism; Activism; Politics and Religion.

Disciplines: Critical Theory, Cultural Studies, Gender and Religion, Study of Religions, Social Anthropology, Intellectual and Political History, Gender Studies, Queer Studies.

Call for Papers: Contemporary Paganisms have had a conflicted relationship with modernity throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Pagan ideologies are interwoven with the political, from the feminist eco-anarchism of Starhawk’s The Spiral Dance, to the conservative racial essentialism of Stephen McNallen. How these representations translate into ethical/political commitments is open to question.

This workshop aims to explore the political discourses of contemporary Pagan religions, whether Witchcraft, Druidry or Goddess spirituality. Questions we offer for consideration include: Is 21st century Paganism oriented towards social change? Is it possible to speak of a unified, coherent Pagan political project? Is there a single moral framework within Pagan thought, or are the ethical implications of different traditions conflicting and contradictory? What challenge might the politics of feminism, postcolonialism, or queer theory represent for Pagan beliefs and practices? How does Paganism respond to global capitalism? And what would a Pagan politics that meets these challenges look, sound, and feel like?

In addressing these questions, this workshop will unite community engagement with an interdisciplinary academic approach, bringing together scholars from social anthropology, critical theory, history, cultural studies and the study of religions into dialogue with activists and authors within the Pagan community.

Convened by a new community of pagan scholars, Generation Hex will seek to examine these issues in the course of a day-long workshop.

Lunch and refreshments provided.

Format:

The one-day workshop will include the presentation of at least four papers (solicited via an open Call for Papers) given by academics who have expertise in the themes mentioned above. Each paper will be followed by a roundtable discussion on the topics raised in the paper by both academics and community activists.

Lunch will be served in the Division’s common room, and will be provided as part of the workshop.

Access:

We hope to provide an accessible and welcoming space for all participants. Information on the accessibility of Division’s buildings is available here; please also contact the conveners directly with any requests for information or assistance.

Workshop Aims:

- To provide critical insights into the present political agency of Britain’s pagan community, informing broader academic debates about the relationship between the political and the spiritual.

- To create an opportunity for junior academics with a background in Pagan Studies to present their work, and receive feedback from their peers and contributors.

- To promote dialogue between Pagan activists and scholars.

- To create a forum for in-depth discussions regarding the future of British Pagan communities, including established figures, future leaders, and academics.

Outputs

- A special edition of a suitable journal (such as The Pomegranate).

Contact Details:

To book a place, please email genhex15@gmail.com. Places are limited, so please do register with us if you would like to attend.

Online Religion: Canaries Don’t Die, They Push the Button

Two stories about religion online have caught my eye today.

The first story deals with the claim by Daniel Dennett of Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Faith Behind that atheist clergy are the harbingers of an age to come when the innermost secrets of religions will be accessible by google search and therefore faith will fall away: Churches Can No Longer Hide The Truth: Daniel Dennett On The New Transparency. From the article: ‘Our digital information age, he argues, is ushering in a “new world of universal transparency” where religious institutions can no longer hide the truth. To survive in an age of transparency, religions will need to come to terms with the facts.’ Of course, ‘Religion’ as a whole has had plenty of opportunities in the past to quote Twain and say “The report of my death was an exaggeration” (also commonly quoted as, “Reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated”). Yes, secularization thesis, I’m looking at you.

I have a couple of issues with this claim. First, the idea that the Internet provides a panopticonic gaze is misleading. Even ignoring issues around accessibility, fluency and technological know-how, the assumption that everything is available online and ‘transparent’ is deeply flawed. I briefly mentioned perception bias in my summary of Paolo Gerbaudo’s talk at the Researching (with) Social Media reading group: Big Data is Watching You: But Does It Understand You? The microscope with which we examine material online is of our own formation, and the so-called ‘secrets’ of religions could still be hidden from a gaze that does not know where to look for them. Or that they even exist.

Second, the assumption that such materials would be intact and whole is also open to dispute. For example, in the case of the Church of Scientology this allegedly panoptic gaze was only directed towards documents about the Operating Thetan Levels when they were unearthed as a result of legal discovery during the 1990 libel case by the Church against Stephen Fishman. But even then they were only available to interested parties like the Press when formal access requests to the clerk’s office were made, which members of the Church attempted to block by making multiple requests of their (see Urban, 2011). That material was eventually leaked online, but it wasn’t until 2008 that a full, unedited version of the materials was hosted online by Wikileaks. Or perhaps we should say allegedly full and allegedly unedited.

Finally, let’s for moment assume that religious ‘facts’ such as the OT levels of Scientology might be present to a hypothetical panopticonic view… Does that mean ding dong the witch of religion is dead?

I think not. Much of my research is on what I have sometimes called pragmatic religions, although ‘Hyper-real’ (Possamai, 2012) or ‘Invented’ (Cusack, 2010) are more frequently used terms within the Sociology of Religion. I describe them as pragmatic because on the whole they are aware of the ‘facts’ of their origins and believe anyway. So for example, the explosion of interest in Jediism after the UK and commonwealth censuses was not because members were convinced that there was truly a galaxy far far away where the events of Star Wars actually occurred and that the Jedi system that they were adopting was the same as Old Ben Kenobi’s. The real world Jedi pragmatically accept the fictional origins of their religion, but adhere to it because it works for them. Likewise, many Wiccans accepted sometime in the 1980s that Gerald Gardener was more likely mocking a local Women’s Institute doyenne when he made Dorothy Clutterbuck the head of his allegedly rediscovered Witches Coven in the New Forest. The Old Religion as described by Margaret Murray and expounded upon by Gardener was perhaps better described as a “Thing of spirit, not of heritage” as Gannon and Field characterised it in Quest Magazine in 1992.

Could the so-called ‘mainstream’ religions respond pragmatically to the revelation of their ‘facts’? Some Christians already do, in the light of the Historical-criticism turn in biblical studies, and seek metaphorical rather than literal truths in their texts. Of course biblical literalism has its contemporary adherents as well. But it seems to me that Dennet is rather lumping all religions and their responses together to deduce the death of religion, with his atheist clergy as the “canaries in the coal mine”. He does end the interview with a reframing of religion as a benevolent charitable endeavour that might survive if it can frankly acknowledge the mythic character of its creeds. Although he is doubtful whether that can be done, “but I hope it can” he says finally.

The second story is about a button.

The connection between these stories that I’m drawing out might not be immediately obvious, but first here’s what the button is. On April’s Fools Day 2015 a single electronic button was added to the Reddit site that has a timer next to it, counting down from 60 seconds. Every time someone (a member of Reddit whose account predates April 1st) presses the button this counter restarts from 60. Depending on the number of seconds left on the counter the pusher receives a different colour of ‘flair’ next to their Reddit account name. Those who have never pressed it have grey flair. Those who pressed it between 60 and 52 seconds get purple flair, between 51 and 42 seconds get blue, between 41 and 32 get green. Those pressing it under 32 seconds have so far received yellow flair, but there are rumours of orange and red flair for under 21 and 11 seconds respectively*. It is not known what will happen if the timer is ever allowed to run out.

I am indebted to Nick Parke, Director of Inform, for bringing this story to my attention, and for our subsequent conversation via e-mail about how people choose to spend their free time online, and the competitive and reputational aspects of this button. Like many activities that are taking place online the ‘newness’ of the media inclines people to see the activities as ‘new’ as well. Whereas, I argue that the Internet is only providing new places in which to be human. And if you don’t think humans haven’t enjoyed seemingly nonsensical competitions for reputation that only matter within small communities then you have never met a trainspotter before. I grew up with a trainspotting/train memorabilia collecting father so I speak from some experience.

However, after I had been discussing this story with Nick I came across a follow up article that makes the story even more relevant to my research: People Got So Into This Strange Internet Button They Made Up a Religion . It seems that the different types of flair are now being translated into religious positions: “The Followers of the Shade” who deliberately won’t press the button because they want to see what happens when the timer runs out. The “Redguard” are intent on only clicking when the clock is about to run out. “The Hitchhikers” tried to press the button at 42 seconds as a tribute to Douglas Adams’ Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy.” The button is providing the hook for some ideological and metaphysical positions and claims are being made for religious status, including the creation of prayers for the different factions, such as the Prayer for the Followers of the Shade:

“Non-pressers we shall be, For Thee, my Shade, for Thee. The Grey hath descended forth from Thy hand, That our flair shall be testament of Thy command So we shall flow a river forth to Thee, And teeming with violet shall it ever be. In nomine Patris, et umbra, et sanctum cinereo.”

Again, the different ‘denominations’ of the button religion (‘Buttonism’? ‘Buttonianity’?) are well aware of the origin and facts of the button. The article asks whether this is a case of role-playing rather than religion, a question that has also been raised of Jediism which can overlap with both the Star Wars fandom and it’s live, game and table top role playing adherents. The article refers to what it terms online micro-religions such as Kopimism, on which I saw a fascinating paper presented at AAR 2014 by Shannon Schorey, which is less fandom based. But it also cites Bronies and other groups that might be moving across the permeable membrane between fandom and religion. The typological lines between these groups are very hard to draw.

Where these pragmatic religions go next is unclear and I am loathe to offer predictions. But, returning to the first story, the effect of the Internet on religion as a while might not be as simply destructive as Dennett argues. Instead we can see it as a potential space for religious creativity, and yes, even for religious play.

*Reddit members have now achieved orange and red flair

Cusack, C. (2010) Invented Religions Imagination, Fiction and Faith, UK: Ashgate

Possamai, A. (2012) (ed.) The Handbook of Hyper-Real Religions, Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion

Urban, H. (2011) The Church of Scientology: A History of a New Religion, USA: Princeton University Press

The Game of Turtles

WARNING: CONTAINS ASOIAF/GOT SPOILERS!

This post is a response to Ethan Quillen’s post (here) about the changes being made in the adaptation of the book series A Song of Ice and Fire (henceforth, ASOIAF) as it is made into the TV series, Game of Thrones (GOT) by its producers, David Benioff and D. B. Weiss (known as D&D… as much as I dislike the connection between these two chaps and my favourite tabletop RPG this is the common signifier for them in the online fandoms for ASOIAF and GOT).

I have written on this blog before about ASOIAF with regards to the internal theology and cosmology of the series and how G.R.R. Martin (GRRM) seems to have an evolutionary view of the development of religion on ‘Planetos’ (here). This post moves beyond religious studies per se to consider the nature of adaptation as Quillen has linked the adaptation of fiction to the work of the ethnographer, and my new religious studies research is primarily ethnographic in nature.

A quick biographical aside, and this is not an attempt to blow my own horn, I must also point out that I have a degree from the National Film and Television School in the UK in Script Development, which involves working with screenwriters, producers and directors on their ideas and scripts, as well as guiding the development of adaptations from original works such as books. As a screenwriter I have also worked on adaptations. So I also have a grounding in the theory and practice of adaptation.

However, before I address Quillen’s post I want to tell you a story… its a story that’s been told before. In fact this story has existed in several forms already. First, it was the experience of the person who first recounted it. It was then the story that he shared with a journalist, who then reported in in some form of media. I then read the story, and now I recount it again in my own words. Therefore, its a story that’s been through several stages of adaptation… and my decision to present it here should indicate that I at least partially agree with Quillen’s discussion of adaptation. I do not deny that adaptation occurs in the retelling of experience or fantasy, but I have another point to make subsequently. However, if you are sitting comfortably, I will begin…

Once upon a time there was a young boy called George. George was a very clever boy, a very imaginative boy, a boy with a big heart. George was a boy who loved turtles.

He loved turtles so much that he kept a few in a big clean terranium, with a lovely stone castle for them all to live in. Sadly, as clever as George was he couldn’t always keep his beloved pets alive. Some mornings he’d get up from his bed, dash over to say good morning to his green skinned friends… and find that yet another of them was on their back at the bottom of the tank. While the others were still happily breaking their fast in the great hall of the castle, innocent smiles on their beaks, another of their number had gone to a better place. But George grew suspicious of their happy smiles… he began to write a story about how the turtles were in a contest for the castle, and that the losers were being killed off in sinister plots in a dramatic war of succession.

Years later young George R. R, Martin would write a fantasy series called A Song of Ice and Fire… the turtles havent made an appearance in this yet (although he does wear a turtle brooch on his famous fisherman’s hat). The fantasy in George’s mind became the story of the Game of Turtles, which was in time adapted into the Game of Thrones (ASOIAF), an example that supports Quillen’s post.

However… there is a reason why the Game of Turtles is different to ASOIAF. GRRM could have stuck with the turtles and written a quaint, if a little blood thirsty, children’s book about a fantasy world populated by turtle knights and lords. But GRRM wanted to write a fantasy series in the mould of Tolkien and the other greats, one that was publishable and likely to be read widely, even if it was also one that played with some of the fantasy/medieval tropes that had become ingrained in popular culture. Adaptation is not a neutral project… GRRM took his initial ideas about scheming turtles and they evolved and developed as he became a professional writer. And being professional means operating within a paradigm (in this case, fantasy literature) even if you try to tease a little at the expectations of that paradigm.

Returning to ethnography we can see a similar working within the boundaries that GRRM’s adaptation demonstrates. Quillen quoted Geertz to support his #everythingisfiction/#everythingisadaptation thesis, so I think it is only fair if I bring in some Rabinow… with regards to his early works, Rabinow explains that he sort refuge in the mode of professionalism expected of the ethnographer: “I guarded myself with the devices offered by my science and with a certain forced naiveté” (Rabinow, 1977:44)

Likewise, Edith Turner explains that her husband’s work on liminality was initially dismissed in Academia in favour of Durkheimian theory because the latter looked like “Good, clean, anthropology” (E.Turner, 2006: 39). Victor Turner eventually found a space for his discussion of liminality, but this came years after he had resigned himself to being “steadily mainstream”… “because of our three children and the matter of jobs”, Edith says (E.Turner, 2006: 37). The ethnographer’s adaptation is as prone to commercial expectations as the fantasy author’s is.

And GOT…? Quillen is correct in describing me as an insane fan of the books. It is an obsession, I’ll admit that. But as mentioned, I have also been a professional writer of adaptations, so I know about working within the paradigm in order to produce commercially viable products off the back of original works (yes, yes, ‘original’ is a misnomer if EVERYTHING is an adaptation). But my problems with the GOT adaptation are because they are working on the basis of an older paradigm where the audience is assumed to be… well… stupid.

Quillen also linked to this blog post in his post: http://gotgifsandmusings.tumblr.com/post/115991793402/unabashed-book-snobbery-gots-10-worst. But I’m not clear on whether read it, because this post is less about stamping feet in a tantrum about what has been left out than what themes have been corrupted by D&D’s need for muddled monologuing (that is meant to serve to signal who the audience should think is the bad guy is in a particular scene, a la the James Bond films perhaps) and the whitewashing of D&D’s favourite characters. Such as…

I just (insanely, perhaps) think that the audiences could have coped with a more nuanced show with complicated characters.

Likewise, if you’ve ever come across the Honest Trailer for GOT you’ll have seen a summary of the number of “BEEWBS” in the show. I’m not a prude… some of them are quite nice if you like that sort of thing. But the paradigm that D&D are working with allows far less space for women in particular to be the intriguing characters that GRRM intended. GRRM, the author who complains about the lack of strong women in Tolkien. GRRM who used the Beauty and the Beast trope in ASOIAF but reversed the genders (Jaime and Brienne). GRRM who created a fantasy loving ‘fair maid’ character and then had her obsess over a man with PTSD and a drinking problem who spits on knights, while being the best of them. But back to GOT: the following is a list of changes made by D&D that directly diminish the role, complexity and importance of female characters in the show (THIS IS VERY SPOILER HEAVY!! YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED) (taken from http://shakspeare.tumblr.com/post/100824969643/whilst-everyones-getting-pumped-for-season-5-i )

“whilst everyone’s getting pumped for season 5, I think we need to remember a couple of things

- don’t forget lady stoneheart. don’t forget that the show runners actively decided to cut one of the most powerful character arcs of the book and force her, instead, into the nagging mother stereotype

- don’t forget arianne martell. don’t forget that it looks like the show runners actively decided to cut a powerful, feminine, kick ass woman of colour, who was next in the line of succession

- don’t forget that her storyline was all about liberating myrcella and crowning her under dornish law, where women have the same inheritance rights as men, and aren’t passed over in favour of their younger male siblings. don’t forget that her entire storyline focused on females empowering other females.

- don’t forget that it looks like they’re giving that same storyline to her younger male sibling, who they have gone out of their way to age up so he fits the role, and the story will now probably be “dashing young prince-to-be kidnaps damsel in distress”

- don’t forget the jamie/cersei rape scene. don’t forget that the show runners actively made the decision to change the story and make that scene include rape.

- don’t forget that mance rayder had a wife called dalla, and that she had a sister called val and that they were both important leading characters in jon’s story. don’t forget that the show runners actively made the decision to cut them out.

- don’t forget the totally unnecessary changes to bran’s storyline. don’t forget the fact that rape and abuse just became part of the background set for most of those scenes. don’t forget that the show runners were on set, actively deciding that those scenes needed a little more male on female violence in the background.

- don’t forget that natalia tena wanted osha to have a pubic wig because when the fuck would a wildling women shave her vagina and the show runners actively told her that wasn’t allowed.

- don’t forget that they created a female character just to serve as a frequently nude prostitute, and that when the actress, esme bianco, refused to do any more nude scenes, the show runners fired her

- don’t forget that she was then killed off in the most sexually violent, brutal, and demeaning way possible

- don’t forget chataya and alayaya, a mother and daughter who were strong, sexual, and unashamedly so, and ran their own brothel. don’t forget that the show runners cut them out, too. don’t forget that the show runners have no problem with sex and prostitution so long as it’s on a man’s terms, and as soon as women are making the decisions, they don’t like it.

- don’t forget that this show we love and watch and support perpetually goes out of its way to instigate violence against women, to take away their agency, their character, their rights, and their abilities. don’t forget that the show runners consciously make the decisions to demean women and use them as a way to dress the set. don’t forget that they take stories from women and give them to the men. don’t forget that they do not support and respect women the way we support and respect their show.”

TL:DR version: women are deleted/forgotten/raped/simplified.

And this also happens to male characters. Just one example: Loras Tyrell is one of the best warriors in the Seven Kingdoms in ASOIAF. But you might have forgotten that since he spends all his free time shagging a prostitute character who wasn’t even in the books, getting down to it very, very soon after the love of his life dies… the one who he is still mourning in the books.

Remember him saying this line about Renly after he died in the show? No? Oh that’s because Loras was too busy showing Olyvar his Dorne shaped birthmark in bed… which might just be one of the laziest last minute plotting devices I’ve ever seen thrown into a TV show!

Or maybe he was too busy talking about fashion. Because he’s gay, Did you get that audience? HE’S GAY!!! (thanks D&D, we couldn’t have known that because he was in love with a man, we had to hear about his love of fringed sleeves). Again, D&D are adapting the series on the assumption that the audience is far more stupid than it actually is.

To summarise, I think GRRM’s decision not to write The Game of Turtles series of books was the correct one, it was just a far stronger story with humans in the key roles, and more commercially viable. However, the assumptions driving D&D’s adaptation are driven by their conception of what we want to see: that beewbs sell, but complex characters don’t.

Quillen’s overall point that everything is an adaptation is not necessarily incorrect. It is merely partial. There is no such thing as a neutral adaptation, either in fiction, or in ethnography as we try to fit our work into the professional niche. We just have to make sure that we are not underestimating our audience and filling our ethnography with the fieldwork equivalent of “Beewbs” instead of doing the source material justice.

References:

Rabinow, P. (1977) Reflections on Fieldwork in Morocco, Berkley: University of California Press

Turner, E. (2006) “Advances in the Study of Spirit Experience: Drawing Together Many Threads” at the Society for the Anthropology of Consciousness, Distinguished Lecture, American Anthropological Association Meetings, San Jose, 2006 [available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1525/ac.2006.17.2.33/pdf]

‘Big Data is watching you. But does it understand you?’

My new blog post about @paologerbaudo’s talk on the Big Data turn, on @DrEllaMcPherson’s research page:

Big Data is watching you. But does it understand you?

126 Characters in Search of an Author: Twitter and Thinking Out Loud on Social Media, the case of the Indigo Children

THE MANAGER

But what do you want here, all of you?

THE FATHER

We want to live.

THE MANAGER (ironically)

For Eternity?

THE FATHER

No, sir, only for a moment… in you.

These lines are from Luigi Pirendello’s 1921 metatheatrical play, Sei Personaggi in Cerca D’autore (“Six Characters in Search of an Author”) where six unused and forgotten fictional characters insist on being put on stage during the rehearsals for another Pirendello play, Il Giuoco Delle Parti (“The Rules of the Game”). On Twitter the ‘rules of the game’ include the limitation of tweets to no more than 140 characters. To maximise the amount of information and connectivity in a tweet an author can use social media ‘tricks’ such as automatically shortened urls, hashtags, and acronyms.

In this paper I argue that when a tweet is significantly shorter than 140 characters, only 14 for example, questions arise for the researcher. First, what is the motivation of an author who writes a tweet that is ‘missing’ 126 characters? Second, why are they choosing to use Twitter for their text? This paper will examine the abbreviated tweets made by members of a loosely bounded community of New Agers in order to consider the ways in which Twitter is put to work by authors allegedly in control of their characters in a medium that enables a shortened route between thinking and publishing.

During my digital ethnographic research on the Indigo Children, a concept from within the New Age Movement whose adherents are geographically disparate but socially networked through the internet, I encountered many tweets containing just 14 characters: just “Indigo Children”. Interviews with these authors through Twitter and by e-mail provided insight into the public/private double mindedness of the Twitter format that enables thinking out loud with increasingly mobile technology and near immediate posting times.

Interviewees also readily drew my attention to the place of the apparently white middle class Indigo Child concept within a wider black Hip Hop culture, and “shoutin’ out” or “reppin’” were among the reasons given for the 14 character tweets. Reppin’ or Representing is done by individuals “constructing self-definitions to elevate their social status and align themselves with desirable persons, places, or things (e.g., friends, neighbourhoods, clubs, clothing brands etc.)” (Stokes 2007). The sympathy between the entrepreneurial, self-making model of the Hip Hop mogul and the conception of the Indigo Child as an evolved form of humanity influences these kind of abbreviated tweets. Finally, as a tweet can be a momentary post forming a part of a larger conversation as an “ambient audience” of followers (Zappavigna, 2012) absorbs the post and reacts to it, the role of louder thinking, or ‘shouting’, to get attention for posts will be considered, with reference to the growing Attention Economy online (Bergquist and Ljungberg, 2001).

Bibliography

Bergquist, M. and Ljungberg, J. (2001) “The Power of Gifts: Organizing Social Relationships in Open Source Communities” in Journal of Information Systems, (2001) 11, 305–320

Stokes, C. (2007) “‘Representin’ In Cyberspace: Sexual Scripts, Self‐Definition, and Hip Hop Culture In Black American Adolescent Girls’ Home Pages”, in Culture, Health & Sexuality: An International Journal for Research, Intervention and Care, 9:2, 169-184

Zappavigna, M. (2012) The Discourse of Twitter and Social Media, London; New York: Continuum International Pub. Group

This comment hardly denies risk, it just assumes that they can be combatted by other technologies. Technologies perhaps with their own inherent risks…